Monday, October 12, 2015

Bleeder & Bates: Elliptical storytelling via implication and juxtaposition

The process of making a film is as important to me as the content of the film. Every time I make of movie, it is something of an experimental exercise (the title of Blake Edward's 1962 film Experiment in Terror leaps to mind). Most filmmakers start with a script, cast it and shoot it wanting to bring the script's vision to the screen. I am more like an artist painting a model he has placed in a particular setting.

I start with the actors and, knowing the theme of the story I want to tell (and very few of the story events), I begin shooting scenes. I've made my films using actors from my repertory company whose 'signature' or brand I had established and whom I had trained in my Action/ReAction technique. Thus, we were well acquainted. My process was to arrive at a location and as the crew set up, I would dictate the dialogue to the actors who would note it and rehearse among themselves until they were ready to run it for me. I might give them a note or two and then I would shoot it. In this manner, the 'script' was created as we shot the movie.

Films aren't customarily shot in sequence and I might start the production by shooting a scene that would be part of the third act. Given the theme and the characters I'd chosen for the production, I knew the sort of scenes I would need to tell the story and as I wrote each new scene, I was aware of where it would be placed in the story's 'Paradigm' (with grateful thanks to Syd Field). This understanding allowed me to know if it was introductory, part of the rising action or something leading us to the resolution or climax.

My preference in storytelling is to imply rather than declare what is going on and you could describe my style as elliptical. I like the audience to draw inferences from what they've seen and come to their own conclusions; I write for an audience that likes to decode that which they've seen going against the old maxim of 'Tell your audience what you're going to tell them. Tell them. Then tell them what you told them' style of filmmaking.

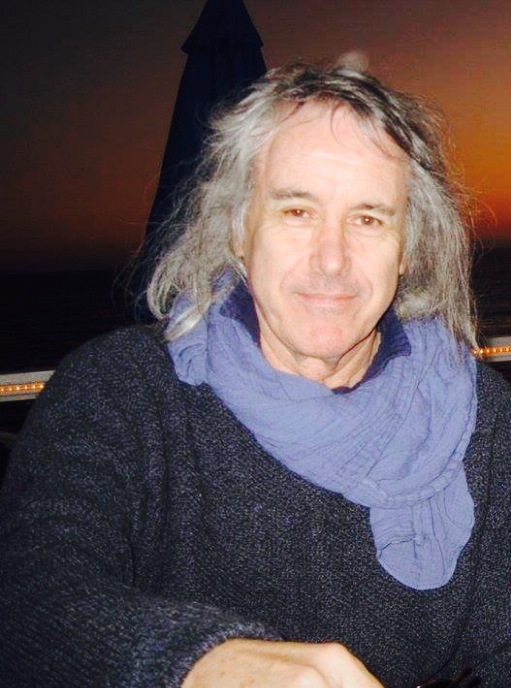

In the sequence I've posted here, one can witness the elliptical and implied nature of Bleeder & Bates. We meet the enigmatic artist (Hal Singleton) and his girlfriend/model (Jeanine Anderson) in a scene without introduction but an implied sense of tension and foreboding. We then move on to the coffee room at L.A.P.D. where Bates (Gregory Brown) is getting himself a coffee but is 'buttonholed' by another detective (I don't remember her name but will edit my blog post to include it when these visual transcriptions reach the end credits). From the nature of her reactions, we perceive she has intentions towards Bates that, for whatever reasons, aren't reciprocated. We can see he doesn't want to stay but politeness keeps him from leaving immediately. Nothing revealing is said; much is implied. Before a conversation can develop, Bates is called away to his relief and her frustration.

Del (Kip Parrott) gives Bates a tipster's letter that will send him on his way to meet the artist. But first...

Detective Carbone (Jack Caputo) is told by an L.A.P.D. employee (Anita Wilson) that a high echelon commander wants to take him to lunch. His reaction tells us how out of the ordinary this is and, further, that he does not relish attention from the high command. Lunch, at the Pacific Dining Car restaurant on 6th Street in Los Angeles, follows this scene and the undercurrent of tension and mistrust is palpable yet unexplained. All we learn is that Commander Rogers (Joe Filbeck) wants Carbone to take Bates to lunch. Then we move on to...

Bates arrives at the artist's loft in the warehouse district of Los Angeles. As he enters and inspects the paintings that are of a dark and macabre nature like the artist himself, the tone is set for what is to follow. The clues provided by the artist will set Bates on the wrong path but will, ironically, be the key to the mystery of Bleeder's murder. Halfway through the conversation, Bates is surprised by the appearance of the girlfriend/model whose presence he hadn't suspected. The ending of this scene reveals that she has an agenda of her own though we don't yet know what it might be.

It took me about nine months to make Bleeder & Bates shooting about two days a week. I kept an outline of the story as I filmed it which allowed me to see where the gaps were that needed filing. Some gaps I intentionally left blank trusting the audience to fill them in on their own. The juxtaposition of one scene with another often served to create a complete thought that the individual scenes were not intended to convey.

This is not the sort of screenwriting or filmmaking technique that would ordinarily be found in a film school curriculum but, back in the day, people from all over the world came to me in Los Angeles to learn this method of making movies at my somewhat unorthodox film school.

[Sequence digitized from VHS copy of time-coded workprint]

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment